Greta vs Trump, and the oldest lie about anger

The idea rage belongs to men – and is shameful for women – is both an ancient and stubbornly persistent one

First of all, sorry I haven’t posted in a while. Not that anyone was complaining, but as a journalist you’re forever conscious of deadlines, even imaginary ones. It’s been three weeks since Good Anger was published, and I’ve wanted to sit back a little and reflect. There have been great pieces about the book in the iPaper, Guardian, Financial Times and elsewhere, as well as some early feedback from readers which has been a thrill to watch.

Anyway. I have become, perhaps unsurprisingly, highly attuned to conversations about anger in the news, and a little while ago one played out between Donald Trump and Greta Thunberg that perfectly captured one of the biggest and most harmful misconceptions about rage.

Let me start by saying: I love Greta Thunberg. Not just for being on the right side of history or being lowkey hilarious, though she is both. It’s the way she effortlessly triggers so many of the most insufferable, insecure man-children in public life. Ever since she was a schoolgirl sitting outside the Swedish parliament in her yellow parka in 2015, holding a placard and peering into the camera with precocious fury, Thunberg had struck terror in the timid hearts of men like Lindsey Graham, Andrew Tate and former Australian PM Scott Morrison. There’s no bigger red flag than an instinctive hatred of a strong-willed 22-year-old woman trying to improve the world because it feels like she is ‘lecturing’ you. Greta is basically a living wrong ‘un-detector.

Which leads nicely to Trump. Recently, the president was asked to comment on Thunberg charting a flotilla of baby formula and medical supplies to Gaza – a protest stunt that ended on 9 June when Israeli forces seized the boat in international waters. Usually, Trump exhibits the bully’s instinct for finding the jugular. But Thunberg – delightfully – seems to scramble him. “She's a strange person,” was the best he could muster for reporters, “she's a young, angry person,” before suggesting she should take an anger management class.

Built into Trump’s effort to shame Thunberg is perhaps the oldest prejudice in the world when it comes to anger: the idea that it belongs only to men. This is based on two things. First, the unhelpful conflation between anger (a natural, healthy emotion) and aggression and violence (a behavioral choice), which men are more prone towards for a variety of reasons. Second, the idea that confidently and directly communicating anger is ‘unladylike’, which goes way back (in Classical Greek thought, men’s anger – orge – was hot-blooded and immediate while women’s anger – cholos – was cold and delayed). Even today, in some parts of Europe, young girls are told they shouldn’t show anger because it ‘detracts from beauty1’ (young boys, of course, are told nothing of the sort).

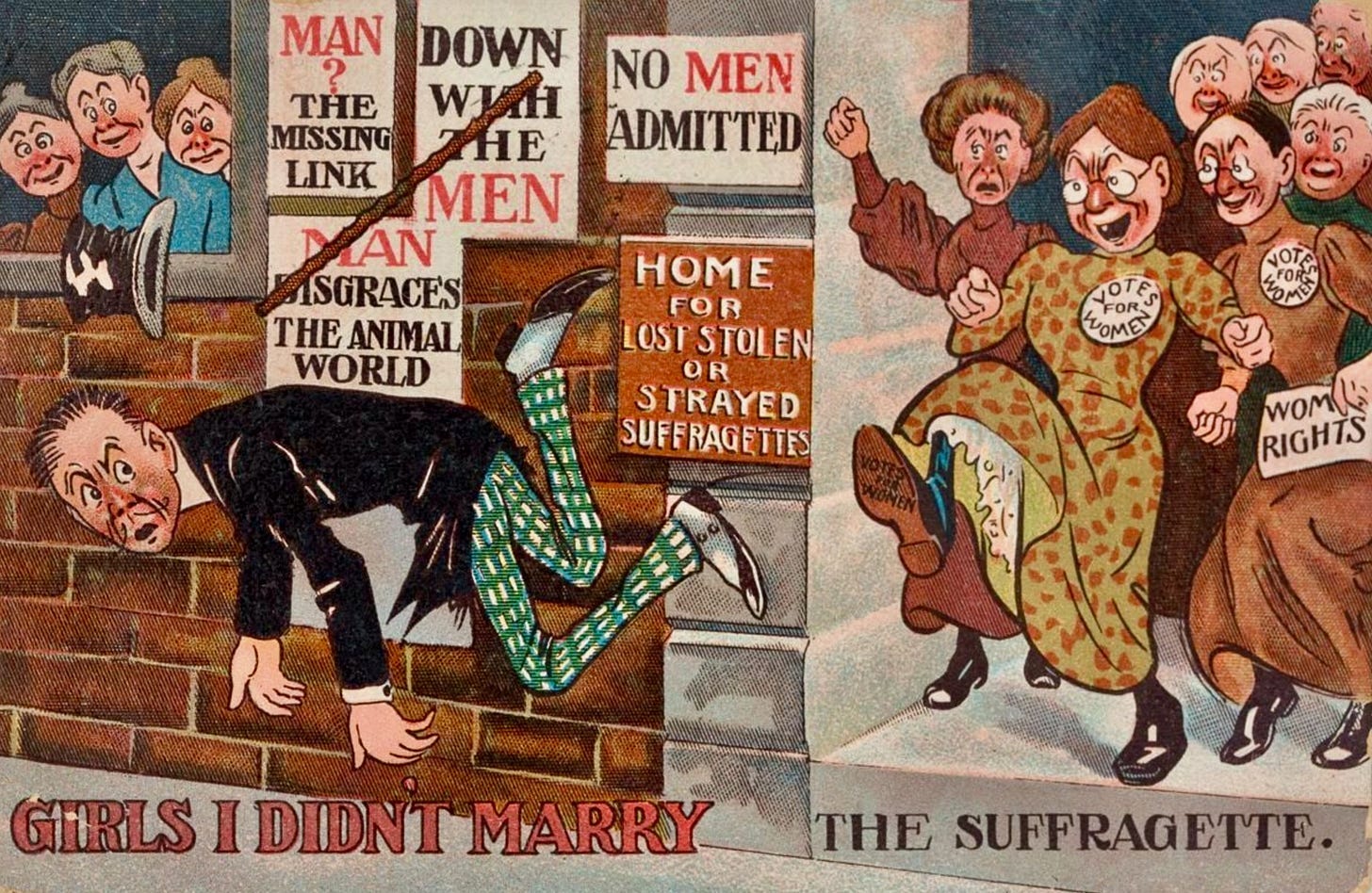

In politics, the stereotype of the ‘raging harpy’ has been used to shame and delegitimise women for centuries. The suffragettes were caricatured as crazy and ugly because they were angry; in the last US election, Fox News regularly ran stories about Kamala Harris’s ‘angry speeches’ as though that alone was an effective smear (which to some it was) – which of course also played into the racist ‘Angry Black Woman’ stereotype.

I’ve been asked a lot in interviews recently: is there any difference between male and female anger? The subtext to this is often: men are angrier, right? Wrong. Research into this topic since at least the 1950s, by the American psychologist Arnold H. Buss and others, has concluded that while men score slightly higher on verbal aggression and hostility (and much higher on physical aggression) there is no difference between the sexes when it comes to experiencing the emotion itself. Carol Tavris, whose brilliant 1982 book Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion is one long rebuttal of the conventional wisdom around anger, was similarly dismissive of the idea one sex had dominion over the emotion (though she did note wryly ‘each sex thinks the other has cornered the anger market’). Interestingly, according to the most recent Gallop World Polls, since 2022 women have actually opened up a small lead over men in how often they report feelings of anger2. Whether this is down to world events, or just the fact more women feel able to admit to feeling angry today, is unclear.

There are consistent differences, however, in how men and women deal with their anger. One I’ve touched on already: men are more likely to be ‘anger out’-types who blow their lid and get into confrontations. So far, most of the books, courses and public handwringing around anger is aimed at them.

Women, for a variety of reasons, are more prone towards what I call ‘the other anger problem’ in the book: suppression and repression (‘anger in’). This internalised fury results in higher levels of depression, anxiety and low self-esteem, and takes a negative toll on their physical health, too. It’s much more pleasant for everyone else to be around, but is arguably even worse for individuals than being a total hot-head. Despite the fact I’m a man, this was my relationship with anger for decades: dismantling it and starting again is what Good Anger is about. For millions of people, denial of anger sits at the root of their unhappiness. It is the unseen part of an iceberg we are only just learning to talk about.

Greta, predictably, had the perfect riposte to Trump’s lame, old-fashioned jibe. “Well I think the world needs a lot more young angry women” she told reporters, without missing a beat. When I saw that, I punched the air. A major part of the mental health revolution of the past decade has centred around teaching boys it is OK to be sad. It is no less vital we start teaching young girls it’s OK to be angry.

Elements of this post have been adapted from the chapter ‘Who Is Allowed To Be Angry?’ in Good Anger

Good Anger: How Rethinking Rage Can Change Our Lives is available in shops now, or can be ordered online at Amazon or Waterstones.