How to channel 'fuck you' energy

Anger spurred Aston Villa striker Ollie Watkins to score against my team at the weekend. It was a reminder of the power of a particular form of fury

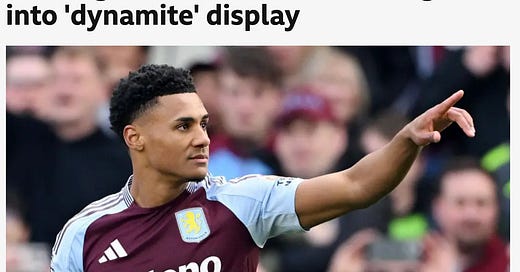

As a Newcastle fan, last week’s 4-1 defeat away at Aston Villa was a painful watch. But it contained a beautiful reminder of how anger can be used for good.

After the match Villa’s striker Ollie Watkins was asked about returning to the team after being left on the bench for a recent high profile European game against Paris Saint-Germain.

"I am not going to lie, I was fuming that I wasn't playing [against PSG] - I let him [Unai Emery] know that," he told Sky Sports.

Rather than be affronted, Emery – his manager – was delighted. "It's fantastic to be angry and fantastic for him to play like he did [against Newcastle]," he said. Watkins channeled his ‘fuck you’ energy to score against my side inside a minute.

One of my favourite people I interview in Good Anger is Marcia Reynolds, a glamorous entrepreneur in her sixties who went to jail at 19 after becoming a drug addict. While there, her inmates staged an intervention to warn her not to waste her life.

“Those women basically put it in my face,” Reynolds told me during an extremely early morning Zoom call with her cat climbing all over her. “They told me: You have to get out there, you’re the one that can do it.” Three years after her release, she graduated summa cum laude – the highest distinction possible – from Arizona State University. She went on to run global businesses and eventually launch her own successful management company.

She credits the energy of anger with turning her life around – specifically the desire to prove the prison officers, her family and society they were wrong about her. “Anger was the strong emotional launch that put my desire to change into motion. It fuelled the courage to act,” she said in a TED Talk in 2019.

Talking to her was inspiring. “The question to ask is always: what is it that I want to create or change, that’s not happening now? If I don’t understand that, then I simmer in my anger. But once I do understand that, anger can stimulate courage,” she told me. “Fear doesn’t stimulate courage. Hope has a dark side, too: it can be paralysing and keep us in situations that we shouldn’t stay in. But the energy behind anger is so deep. My life was a mess until I activated the power of ‘Oh yeah, I’ll show you!’”

Then there’s the example of Tyson Fury. After achieving his lifelong goal of becoming World Heavyweight Champion in 2015, the boxer’s mental health plummeted. Photographs of him out on the town, always with a beer in hand, became fodder for the tabloids. At 6 foot 9 and now ballooned up in weight to 30 stone, he cut a tragic figure. After two years in the wilderness, Fury’s career looked over. “I hope I die every day,” he told the press.

A mixture of therapy, faith and family got him on the road to sobriety. But he wasn’t serious about boxing again until one moment in particular gave him the motivation he needed. In his absence, an American called Deontay Wilder had established himself as champion and the world’s most feared fighter. Someone asked Wilder about the idea Fury could return and he mocked the idea. Fury saw a clip of this on his phone one day. “Deontay Wilder spurred me on as he said I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I thought: ‘I’m a fat pig and I need to turn this around, come back and knock him out.’”’ Savouring the anger he felt at being disrespected, Fury got to work. A few months later, he beat him in one of the most stunning and unlikely comebacks in sporting history.

Anger is an emotion that fills us with energy. It triggers a neuroendocrine cascade that floods the body with hormones that prepare it for intense physical action. We can waste that energy by lashing out at others, or ourselves. Or we can channel it into whatever work we need to do to achieve the best possible revenge: success.

Good Anger: how rethinking rage can changes our lives can be pre-ordered at Amazon or Waterstones.