On getting your first book review (plus: a free extract from Good Anger)

My first book – about how embracing a taboo emotion can transform your mental health – is out this week. Read part of the opening chapter here

Someone once said writing a book is like telling a joke and then waiting three years to find out if anyone laughs at the punchline. This, I have discovered, is painfully true.

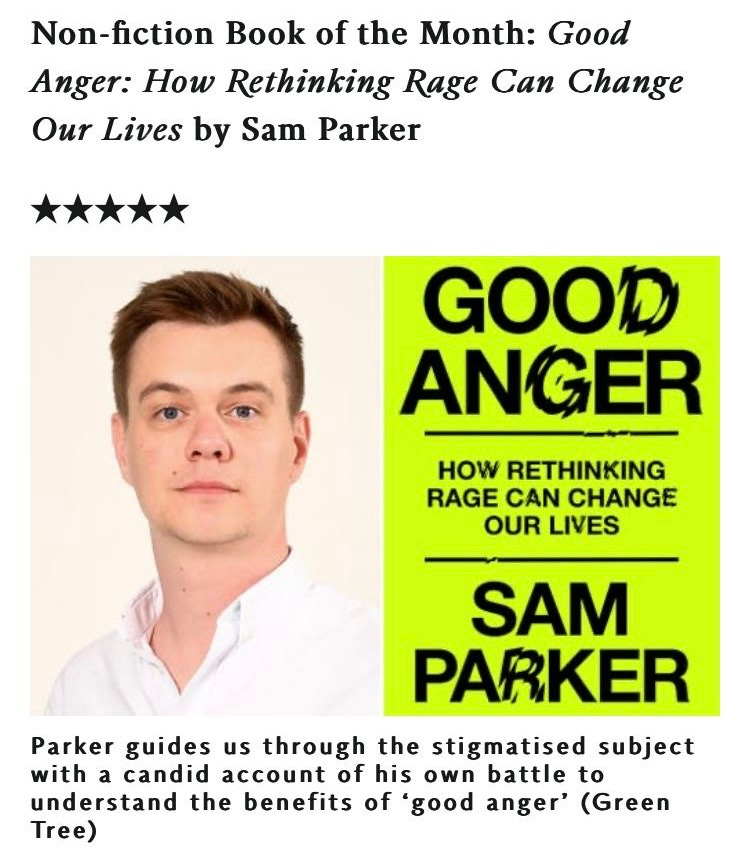

But thankfully the wait is now over. Good Anger hits the shelves on Thursday, and this weekend it was reviewed for the first time. Writing in The Independent, Martin Chilton gave it a full 5 stars and some lovely words: “packed with insight”, “powerful and engaging” and “a potent defence of a vilified emotion”. One story from my own struggles with anger even made him “snort with laughter”, which is oddly healing to read.

To Martin’s kind and thoughtful appraisal, I’ll quickly add a few more early reactions, since reluctant horn-tooting is very much my job this week:

“Enlightening and compulsory”

Dr Aaron Balick, psychotherapist and author of The Psychodynamics of Social Networking

“Wise and quietly revolutionary”

Kate McCann, Times Radio

“A marvellous book which enhances our understanding of ourselves and others”

Irvine Welsh, author of Trainspotting

To celebrate it finally being here, I am sharing a free extract from Good Anger. It comes at the very beginning of the book, and describes the moment when, after a hopeless period chasing the promises of the wellness industry – and a lifetime of people-pleasing and avoiding conflict – I had my first, accidental glimpse of the upsides of rage.

If you enjoy it and would like to read more, the full fat version can be ordered from Amazon or Waterstones or, if you’d like to hear me strain to pronounce the names of some long-dead saints, Spotify and the other audiobook platforms.

Chapter 1 - The other anger problem

In the far corner of a gym in north London, past people pounding running machines beneath silent daytime TV, beyond the doors of the yoga studio where limbs are bent in shaky salutation, away from the weights floor where arms strain metal to the sky, a black bag filled with sand hangs crookedly from the ceiling.

I make my way over to it in a tatty old pair of running shoes, some shorts and a T-shirt I usually wear to bed, and perform warm-up exercises I remember from PE lessons in 1997: swinging my arms in wide circles, circling my hips to an imaginary hula-hoop, touching my toes (read: lower kneecap) with the tips of my fingers. Then I pull out the gloves.

The gym was always busy, but I’d only seen one other person use the punch bag. Like me he was in his 30s, perhaps a little older, and he stepped around it in slow, easy movements, his head rocking left to right like a metronome, releasing small flurries of punches that carried the unmistakable ring of accuracy you hear in all sports when they’re done properly: a golf ball hit cleanly, a tennis serve destined to go unanswered, a free kick whipped into the top corner of the net. He stepped back and gave me a small nod that meant I could share the bag with him, then watched with pity as I planted my feet squarely and began slapping at it like a bear cub trying to catch a salmon.

‘Get some lessons, bro,’ he said to me with a gentle pat on my shoulder. And so I did. Every Tuesday at 7 a.m., I went to a class in my local park and learned the basics of boxing. How to throw a jab, hook and cross, straight and true at the wrist, pivoting from good anger 2 1 0 1 the feet and hips. How fighters angle their bodies sideways, stay on the balls of their feet and keep a hand up to protect their chin at all times. I progressed from the clueless stage to someone who at least understood the theory of what he was doing.

Back at the gym I never saw the man again, or anyone else in the corner at the punch bag, but even though the runners and the yogis and the weightlifters never gave me a second glance, I always felt awkward and self-conscious when I made my way over there. Maybe it was the fact that I kept catching sight of my stomach in the mirror, quivering over the hem of my shorts like a toddler’s lip in the seconds before they cry. Maybe it was the fact that I was boxing, a sport I’d barely taken an interest in before and doing it made me feel like a cliché: a sporting mid-life crisis from a man who had barely been in a fight in his life. But I also knew I was in a fight – with myself.

I had been in a dark and desperate place for months. My career had stalled and was starting to fall apart. Key relationships in my life had broken down completely. Anxiety, something I had battled with since I was a child, was back, making each day a duel with doom and panic. I wasn’t eating or sleeping properly, couldn’t hold a conversation with my partner that didn’t involve outlining all the catastrophes forming in my head. My confidence – in myself, in life – had faded to almost nothing.

More than anything, I just wanted to relax. And so I spent months following the call of the wellness industry and its soothing social media gurus. I tried meditating in my bedroom on a small cushion next to an open window, gently bringing my panicked thoughts back to the rhythm of my own breath. I journalled each morning, listing the multitudinous reasons I had to be deeply grateful. I practised mindfulness as I went about my day, focusing on the wind as it brushed my cheeks and the birds chirping in the trees. Deep breathing exercises of various lengths and formations. Cold showers. Reading to calm my thoughts. Listening to music to lift my thoughts. Running up and down the road to tire my thoughts out. Reframing my thoughts to myself as though I was my own best friend. All of it just felt like cosplaying a person with inner peace. The moment I took off whatever costume I had on, I was back to being me again: the most anxious man in the world.

Boxing had been just one more random roll of the dice. If nothing else, I thought it might tire me out and force my mind and muscles to sleep. And then, around the ninth or tenth time, something strange happened. Like most days, I woke up not wanting to get out of bed, but I dragged myself to the gym and set about the punch bag in my usual, sheepish way, trying to be disciplined with the shape of my arms and feet, trying to throw my fists as cleanly as I could.

About 10 minutes into the routine, I began to feel a strange sensation rise up from the pit of my stomach, travel down my arms and into my hands. I started punching, not with any greater accuracy, but with a strength and energy I’d never felt before. The more I hit the bag, the more I had a sense of myself growing taller and wider. My swings got bigger. I was throwing my entire body into them now, aiming not at the bag but through it, grunting each time my gloves hit the leather. I must have looked strange – ridiculous, even – to anyone who had bothered to look over. But for the first time, I didn’t care. I just punched and punched, barely pausing for breath until almost an hour had passed. When I stopped I realised my eyes were wet with tears.

Bent over, gasping for breath, I could still feel the sense of power tingling all over my body. In my mind’s eye I saw with sudden, perfect clarity the problems making my life a misery. Conversations I had to have to put it all right were blossoming and unfurling perfectly in my thoughts. Bent over in that lonely corner of the gym with a crooked bag of sand swinging inches from my head, I realised for the first time in months I wasn’t sad or anxious. I was furious.

Good Anger: how rethinking rage can changes our lives can be pre-ordered at Amazon or Waterstones.

This is great Sam. Can’t wait to pick it up and read it. Thank you for sharing the first chapter!