Why anger?

On writing a book about the least understood emotion

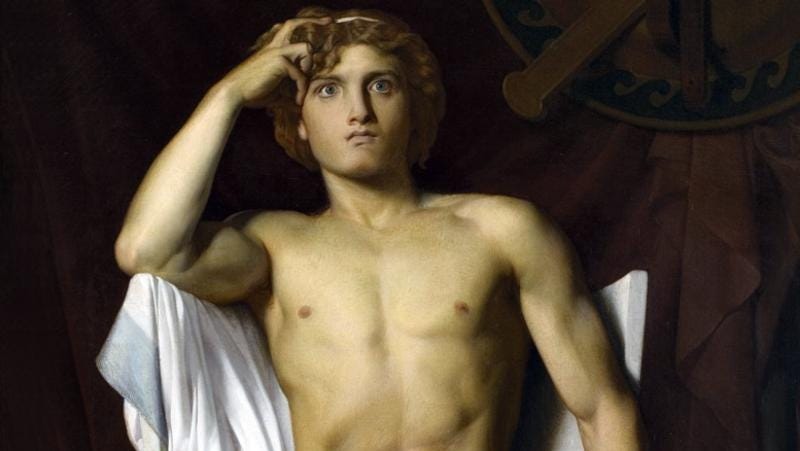

As the historian Mary Beard has pointed out, ‘anger’ is the very first word in western literature. Homer started The Iliad with the title ‘The Wrath of Achilles’, before telling a story of blood, guts and violence that would make Quentin Tarantino blush.

It’s also the subject of one of the earliest surviving texts on philosophy, and arguably the first s…